How is the Eastgate Building NOT like a Termite Mound?

Posted: January 3, 2012 Filed under: Biology Research, Biomimicry Methodology | Tags: bridging biology research to design, deepening biomimicry, eastgate building and lungs, iterative design and science research, strategic research and innovation, termite mound as lungs 8 Comments

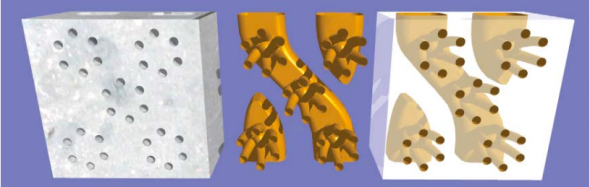

Image from J Scott Tuner and Rupert C Soar - Figure 9 from excellent paper available by clicking the image above.

Why is biomimicry superficial?

Back at the beginning of this blog I wrote an entry commenting that biomimicry does not guarantee sustainability. It was not meant as a critique against biomimicry as a methodology, but rather at those who only wish to learn superficial insights from nature. A recent comment highlighted the complexity of this conversation, when Jamie Saunders commented that “biomimicry” as a term might suggest non-systems thinking;

Might this be supported if ‘ecomicry’ rather than ‘biomicry’ was initially considered ? Co-evolution and ‘ecomimicry’ – drawing a conceptual understanding and insight from the ‘whole’ ecosystem’ – ‘the interwoven systems that can provide “life support” for current and future multi-species inhabitants.’

My answer, in full here, explains that “bios” has always been interpreted by those pioneering biomimicry to incorporate all of life sciences; including biology, ecology, evolutiona and much more. In other words, at all scales and at multiple levels; form, process and ecosystem. Unfortunately, most stories celebrate a form based level of inspiration; velcro for example, and skip over the deeper, more complex stories; such as Paul Hawkins using redwood forests to evolve business models.

Should the Eastgate Building be a Lung?

We've all seen or used one of these images (I'm guilty), but perhaps we didn't really know what we were comparing?

In a poorly titled paper, “Beyond Biomimicry“, researchers dive into the Eastgate Building case study to analyse it from a biological perspective. The insights are fascinating as the research of J Scott Turner and Rupert C Soar suggest the termite mound might not be functioning the way it does due to temperature management, but rather to encourage the flow of oxygen. In other words, it is not a passive heat exchanger, as much as an extension of the organisms’ lungs.

Turner and Soar’s research process is fascinating as it clearly outlines why the Eastgate building is like a termite mound, and then why it is NOT. While they suggest the next step is to move beyond biomimicry, I argue it is in fact time to move further “into” biomimicry. And we need more researchers like Turner and Soar to help designer’s understand what we’ve missed.

Perhaps it is even common knowledge to biologists that a termite mound functions like a lung, but for designer’s who have only “discovered” ant hills through comparative diagrams to the Eastgate architecture, this is eye opening.

Note: I really recommend the paper for some fascinating insights and quotes such as these in the final discussion:

Indeed, the possibilities may be more than large: they may be vast. This is because the termite mound is not simply a structural arena for interesting function. It is itself a function, sustained by an ongoing construction process that reflects the physiological predilections of the myriad agents that build and maintain it. The mound, in short, is the embodiment of the termites’ “extended physiology” …

Iterative Research = Iterative Design

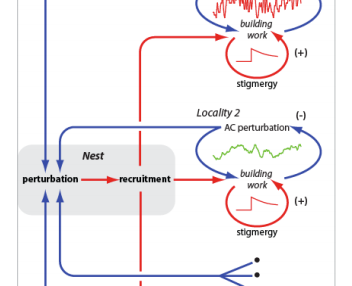

Does any designer out there understand stigmergy? Image from J Scott Tuner and Rupert C Soar - Figure 9 from excellent paper available by clicking the image above.

I love this paper on many levels, but primarily because it fuels an iterative design process. This paper allows designers to look at successful projects such as Eastgate and go further. As pointed out in the paper, there is a lot of room for improvement. Our buildings do not “breathe” like lungs and they are not living, adapting structures. The opportunity exists now for a designer to begin to unwrap the complex diagrams of stigmergy and translate them into a building’s program and construction.

I want more research papers into biomimicry case studies that follow the process of J Scott Turner and Rupert C Soar that discuss:

- How is this [insert case study here] like the natural model(s)?

- How is this [case study] not like the natural model(s)?

In my ideal world, this would fuel design projects that would experiment and apply the subsequent insights of biological systems that would in turn encourage further scientific research. This is not a step beyond biomimicry, but actually genuine integration of the biological research into design process. And it is not impossible to imagine, considering the diversity of information and interest on termite mounds stirred up by the Mick Pearce and OVE Arup; designers and engineers.

Carl – this is great stuff! How did you find this paper?

I have to admit, I have no idea…

It’s been poking around for a little while I think. http://doctorcrowd.wordpress.com/2012/10/20/aluminum-casts-of-ant-colonies/comment-page-1/#comment-21 mentioned it back in October. I used it in my dissertation over summer after Michael Palwyn mentioned it in his book on architecture, and put a section from that up on my blog at the start of December: http://biomimicron.wordpress.com/2012/12/11/biomythology-eastgate-gate-or-how-the-eastgate-centre-harare-is-not-like-a-termite-mound/

The dissertation itself grew off this and started looking critically at other design templates and their possible development. I’ve posted a little else where on the blog, and will probably add more bit’s, including my own data on a similar ant’s nest study as I get the chance.

Love it Carl! Yesssssss! You can practice biomimicry across a wide continuum. Take baby steps and try to use materials that nature would use. Or just focus on shape for a start. Or take it all the way to doing as much as you can to mimic nature.

Of course, that may include making assumptions that later turn out wrong. THAT is why science helps. The more evidence to support a hypothesis of how we think termite mounds are working, the better. However, you have to remember that science is set up to allow new information that changes the hypothesis. Science is not static. Because humans don’t understand everything. Humans learn over time by testing ideas, something both scientists and designers have in common.

So I would say ‘bring it on!’ Continue asking questions about a project claiming biomimicry as an inspiration. How close did the project come to mimicking what’s really happening in nature? The closer we get, the more long-lasting, resilient, and conducive to life on this planet we will achieve.

Baby steps at first. That’s okay with me.

Carl – I totally agree. Often critiques of biomimicry focus on how the solutions arrived at are NOT like the natural systems. We should always be critical of our work and seek to understand how it can be improved,or even how it has totally failed. However, this is how evolution works. Many mutations arise that are of no value to an organism, many are harmful and a few may be useful in some context. Each new trait builds upon the past and is selected for it’s fitness.

To state that we must move beyond biomimicry misses the whole point. Failures are part of biomimicry. To acknowledge them is the humility that we must strive for if we are to progress. In my research as a scientist, I am never “right”, I only hope that I understand a bit more what is “right” than I did before my experiment. Biological systems are complex, dynamic and often chaotic. Any solution we devise through the biomimicry process will never be “right”, but we strive to make it more sustainable than what came before. Baby steps indeed, but how else can we learn to walk.

Organisms are not optimal, we are saddled with many inefficient vestiges of our evolutionary history, we build upon our past and do the best with what we are given. So what, look what all of these fantastic organisms can achieve even when they are not perfect!

Ian

[…] Carl Hastrich/Bouncing Ideas, How is the Eastgate Building NOT like a Termite Mound? […]

[…] and engineering has provoked biologists to investigate the termite mound very closely. As I explore elsewhere, the termite mound more closely resembles the physiology of the organism than the self balancing […]

[…] Hastrich on his Bouncing Ideas Blog asked “How is the Eastgate Building not like a termite mound” and if this type of research will encourage us to dive deeper into […]